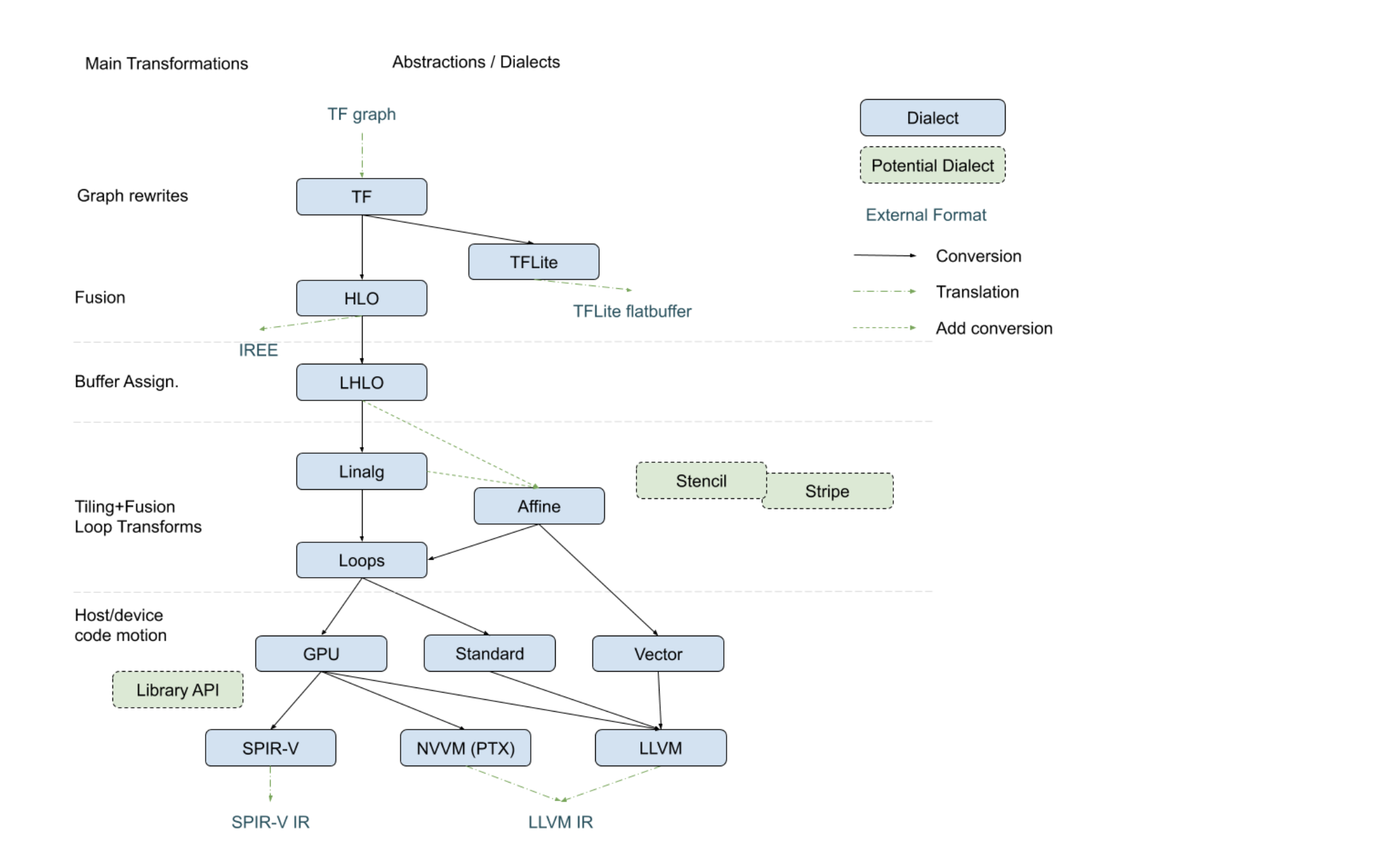

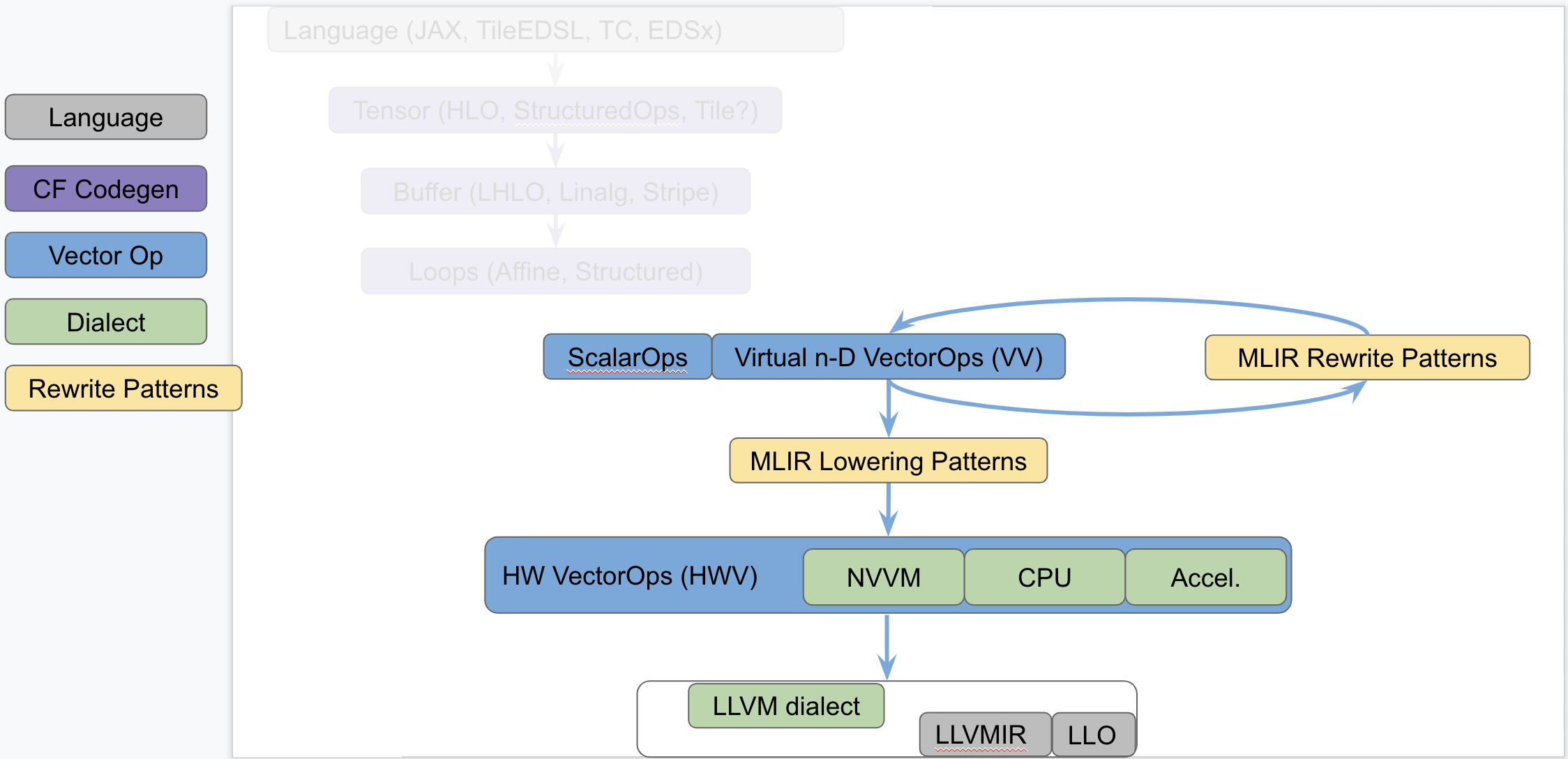

1# 'vector' Dialect 2 3[TOC] 4 5MLIR supports multi-dimensional `vector` types and custom operations on those 6types. A generic, retargetable, higher-order `vector` type (`n-D` with `n > 1`) 7is a structured type, that carries semantic information useful for 8transformations. This document discusses retargetable abstractions that exist in 9MLIR today and operate on ssa-values of type `vector` along with pattern 10rewrites and lowerings that enable targeting specific instructions on concrete 11targets. These abstractions serve to separate concerns between operations on 12`memref` (a.k.a buffers) and operations on `vector` values. This is not a new 13proposal but rather a textual documentation of existing MLIR components along 14with a rationale. 15 16## Positioning in the Codegen Infrastructure 17 18The following diagram, recently presented with the 19[StructuredOps abstractions](https://drive.google.com/corp/drive/u/0/folders/1sRAsgsd8Bvpm_IxREmZf2agsGU2KvrK-), 20captures the current codegen paths implemented in MLIR in the various existing 21lowering paths. 22 23 24The following diagram seeks to isolate `vector` dialects from the complexity of 25the codegen paths and focus on the payload-carrying ops that operate on std and 26`vector` types. This diagram is not to be taken as set in stone and 27representative of what exists today but rather illustrates the layering of 28abstractions in MLIR. 29 30 31 32This separates concerns related to (a) defining efficient operations on 33`vector` types from (b) program analyses + transformations on `memref`, loops 34and other types of structured ops (be they `HLO`, `LHLO`, `Linalg` or other ). 35Looking a bit forward in time, we can put a stake in the ground and venture that 36the higher level of `vector`-level primitives we build and target from codegen 37(or some user/language level), the simpler our task will be, the more complex 38patterns can be expressed and the better performance will be. 39 40## Components of a Generic Retargetable Vector-Level Dialect 41 42The existing MLIR `vector`-level dialects are related to the following bottom-up 43abstractions: 44 451. Representation in `LLVMIR` via data structures, instructions and intrinsics. 46 This is referred to as the `LLVM` level. 472. Set of machine-specific operations and types that are built to translate 48 almost 1-1 with the HW ISA. This is referred to as the Hardware Vector 49 level; a.k.a `HWV`. For instance, we have (a) the `NVVM` dialect (for 50 `CUDA`) with tensor core ops, (b) accelerator-specific dialects (internal), 51 a potential (future) `CPU` dialect to capture `LLVM` intrinsics more closely 52 and other dialects for specific hardware. Ideally this should be 53 auto-generated as much as possible from the `LLVM` level. 543. Set of virtual, machine-agnostic, operations that are informed by costs at 55 the `HWV`-level. This is referred to as the Virtual Vector level; a.k.a 56 `VV`. This is the level that higher-level abstractions (codegen, automatic 57 vectorization, potential vector language, ...) targets. 58 59The existing generic, retargetable, `vector`-level dialect is related to the 60following top-down rewrites and conversions: 61 621. MLIR Rewrite Patterns applied by the MLIR `PatternRewrite` infrastructure to 63 progressively lower to implementations that match closer and closer to the 64 `HWV`. Some patterns are "in-dialect" `VV -> VV` and some are conversions 65 `VV -> HWV`. 662. `Virtual Vector -> Hardware Vector` lowering is specified as a set of MLIR 67 lowering patterns that are specified manually for now. 683. `Hardware Vector -> LLVM` lowering is a mechanical process that is written 69 manually at the moment and that should be automated, following the `LLVM -> 70 Hardware Vector` ops generation as closely as possible. 71 72## Short Description of the Existing Infrastructure 73 74### LLVM level 75 76On CPU, the `n-D` `vector` type currently lowers to `!llvm<array<vector>>`. More 77concretely, `vector<4x8x128xf32>` lowers to `!llvm<[4 x [ 8 x [ 128 x float 78]]]>`. There are tradeoffs involved related to how one can access subvectors and 79how one uses `llvm.extractelement`, `llvm.insertelement` and 80`llvm.shufflevector`. A [deeper dive section](#DeeperDive) discusses the current 81lowering choices and tradeoffs. 82 83### Hardware Vector Ops 84 85Hardware Vector Ops are implemented as one dialect per target. For internal 86hardware, we are auto-generating the specific HW dialects. For `GPU`, the `NVVM` 87dialect adds operations such as `mma.sync`, `shfl` and tests. For `CPU` things 88are somewhat in-flight because the abstraction is close to `LLVMIR`. The jury is 89still out on whether a generic `CPU` dialect is concretely needed, but it seems 90reasonable to have the same levels of abstraction for all targets and perform 91cost-based lowering decisions in MLIR even for `LLVM`. Specialized `CPU` 92dialects that would capture specific features not well captured by LLVM peephole 93optimizations of on different types that core MLIR supports (e.g. Scalable 94Vectors) are welcome future extensions. 95 96### Virtual Vector Ops 97 98Some existing Standard and Vector Dialect on `n-D` `vector` types comprise: 99 100```mlir 101%2 = arith.addf %0, %1 : vector<3x7x8xf32> // -> vector<3x7x8xf32> %2 = 102arith.mulf %0, %1 : vector<3x7x8xf32> // -> vector<3x7x8xf32> %2 = std.splat 103%1 : vector<3x7x8xf32> // -> vector<3x7x8xf32> 104 105%1 = vector.extract %0[1]: vector<3x7x8xf32> // -> vector<7x8xf32> %1 = 106vector.extract %0[1, 5]: vector<3x7x8xf32> // -> vector<8xf32> %2 = 107vector.outerproduct %0, %1: vector<4xf32>, vector<8xf32> // -> vector<4x8xf32> 108%3 = vector.outerproduct %0, %1, %2: vector<4xf32>, vector<8xf32> // fma when 109adding %2 %3 = vector.strided_slice %0 {offsets = [2, 2], sizes = [2, 2], 110strides = [1, 1]}: vector<4x8x16xf32> // Returns a slice of type 111vector<2x2x16xf32> 112 113%2 = vector.transfer_read %A[%0, %1] {permutation_map = (d0, d1) -> (d0)}: 114memref<7x?xf32>, vector<4xf32> 115 116vector.transfer_write %f1, %A[%i0, %i1, %i2, %i3] {permutation_map = (d0, d1, 117d2, d3) -> (d3, d1, d0)} : vector<5x4x3xf32>, memref<?x?x?x?xf32> 118``` 119 120The list of Vector is currently undergoing evolutions and is best kept track of 121by following the evolution of the 122[VectorOps.td](https://github.com/llvm/llvm-project/blob/main/mlir/include/mlir/Dialect/Vector/VectorOps.td) 123ODS file (markdown documentation is automatically generated locally when 124building and populates the 125[Vector doc](https://github.com/llvm/llvm-project/blob/main/mlir/docs/Dialects/Vector.md)). 126Recent extensions are driven by concrete use cases of interest. A notable such 127use case is the `vector.contract` op which applies principles of the 128StructuredOps abstraction to `vector` types. 129 130### Virtual Vector Rewrite Patterns 131 132The following rewrite patterns exist at the `VV->VV` level: 133 1341. The now retired `MaterializeVector` pass used to legalize ops on a 135 coarse-grained virtual `vector` to a finer-grained virtual `vector` by 136 unrolling. This has been rewritten as a retargetable unroll-and-jam pattern 137 on `vector` ops and `vector` types. 1382. The lowering of `vector_transfer` ops legalizes `vector` load/store ops to 139 permuted loops over scalar load/stores. This should evolve to loops over 140 `vector` load/stores + `mask` operations as they become available `vector` 141 ops at the `VV` level. 142 143The general direction is to add more Virtual Vector level ops and implement more 144useful `VV -> VV` rewrites as composable patterns that the PatternRewrite 145infrastructure can apply iteratively. 146 147### Virtual Vector to Hardware Vector Lowering 148 149For now, `VV -> HWV` are specified in C++ (see for instance the 150[SplatOpLowering for n-D vectors](https://github.com/tensorflow/mlir/commit/0a0c4867c6a6fcb0a2f17ef26a791c1d551fe33d) 151or the 152[VectorOuterProductOp lowering](https://github.com/tensorflow/mlir/commit/957b1ca9680b4aacabb3a480fbc4ebd2506334b8)). 153 154Simple 155[conversion tests](https://github.com/llvm/llvm-project/blob/main/mlir/test/Conversion/VectorToLLVM/vector-to-llvm.mlir) 156are available for the `LLVM` target starting from the Virtual Vector Level. 157 158## Rationale 159 160### Hardware as `vector` Machines of Minimum Granularity 161 162Higher-dimensional `vector`s are ubiquitous in modern HPC hardware. One way to 163think about Generic Retargetable `vector`-Level Dialect is that it operates on 164`vector` types that are multiples of a "good" `vector` size so the HW can 165efficiently implement a set of high-level primitives (e.g. 166`vector<8x8x8x16xf32>` when HW `vector` size is say `vector<4x8xf32>`). 167 168Some notable `vector` sizes of interest include: 169 1701. CPU: `vector<HW_vector_size * k>`, `vector<core_count * k’ x 171 HW_vector_size * k>` and `vector<socket_count x core_count * k’ x 172 HW_vector_size * k>` 1732. GPU: `vector<warp_size * k>`, `vector<warp_size * k x float4>` and 174 `vector<warp_size * k x 4 x 4 x 4>` for tensor_core sizes, 1753. Other accelerators: n-D `vector` as first-class citizens in the HW. 176 177Depending on the target, ops on sizes that are not multiples of the HW `vector` 178size may either produce slow code (e.g. by going through `LLVM` legalization) or 179may not legalize at all (e.g. some unsupported accelerator X combination of ops 180and types). 181 182### Transformations Problems Avoided 183 184A `vector<16x32x64xf32>` virtual `vector` is a coarse-grained type that can be 185“unrolled” to HW-specific sizes. The multi-dimensional unrolling factors are 186carried in the IR by the `vector` type. After unrolling, traditional 187instruction-level scheduling can be run. 188 189The following key transformations (along with the supporting analyses and 190structural constraints) are completely avoided by operating on a `vector` 191`ssa-value` abstraction: 192 1931. Loop unroll and unroll-and-jam. 1942. Loop and load-store restructuring for register reuse. 1953. Load to store forwarding and Mem2reg. 1964. Coarsening (raising) from finer-grained `vector` form. 197 198Note that “unrolling” in the context of `vector`s corresponds to partial loop 199unroll-and-jam and not full unrolling. As a consequence this is expected to 200compose with SW pipelining where applicable and does not result in ICache blow 201up. 202 203### The Big Out-Of-Scope Piece: Automatic Vectorization 204 205One important piece not discussed here is automatic vectorization (automatically 206raising from scalar to n-D `vector` ops and types). The TL;DR is that when the 207first "super-vectorization" prototype was implemented, MLIR was nowhere near as 208mature as it is today. As we continue building more abstractions in `VV -> HWV`, 209there is an opportunity to revisit vectorization in MLIR. 210 211Since this topic touches on codegen abstractions, it is technically out of the 212scope of this survey document but there is a lot to discuss in light of 213structured op type representations and how a vectorization transformation can be 214reused across dialects. In particular, MLIR allows the definition of dialects at 215arbitrary levels of granularity and lends itself favorably to progressive 216lowering. The argument can be made that automatic vectorization on a loops + ops 217abstraction is akin to raising structural information that has been lost. 218Instead, it is possible to revisit vectorization as simple pattern rewrites, 219provided the IR is in a suitable form. For instance, vectorizing a 220`linalg.generic` op whose semantics match a `matmul` can be done 221[quite easily with a pattern](https://github.com/tensorflow/mlir/commit/bff722d6b59ab99b998f0c2b9fccd0267d9f93b5). 222In fact this pattern is trivial to generalize to any type of contraction when 223targeting the `vector.contract` op, as well as to any field (`+/*`, `min/+`, 224`max/+`, `or/and`, `logsumexp/+` ...) . In other words, by operating on a higher 225level of generic abstractions than affine loops, non-trivial transformations 226become significantly simpler and composable at a finer granularity. 227 228Irrespective of the existence of an auto-vectorizer, one can build a notional 229vector language based on the VectorOps dialect and build end-to-end models with 230expressing `vector`s in the IR directly and simple pattern-rewrites. 231[EDSC](https://github.com/llvm/llvm-project/blob/main/mlir/docs/EDSC.md)s 232provide a simple way of driving such a notional language directly in C++. 233 234## Bikeshed Naming Discussion 235 236There are arguments against naming an n-D level of abstraction `vector` because 237most people associate it with 1-D `vector`s. On the other hand, `vector`s are 238first-class n-D values in MLIR. The alternative name Tile has been proposed, 239which conveys higher-D meaning. But it also is one of the most overloaded terms 240in compilers and hardware. For now, we generally use the `n-D` `vector` name and 241are open to better suggestions. 242 243## DeeperDive 244 245This section describes the tradeoffs involved in lowering the MLIR n-D vector 246type and operations on it to LLVM-IR. Putting aside the 247[LLVM Matrix](http://lists.llvm.org/pipermail/llvm-dev/2018-October/126871.html) 248proposal for now, this assumes LLVM only has built-in support for 1-D vector. 249The relationship with the LLVM Matrix proposal is discussed at the end of this 250document. 251 252MLIR does not currently support dynamic vector sizes (i.e. SVE style) so the 253discussion is limited to static rank and static vector sizes (e.g. 254`vector<4x8x16x32xf32>`). This section discusses operations on vectors in LLVM 255and MLIR. 256 257LLVM instructions are prefixed by the `llvm.` dialect prefix (e.g. 258`llvm.insertvalue`). Such ops operate exclusively on 1-D vectors and aggregates 259following the [LLVM LangRef](https://llvm.org/docs/LangRef.html). MLIR 260operations are prefixed by the `vector.` dialect prefix (e.g. 261`vector.insertelement`). Such ops operate exclusively on MLIR `n-D` `vector` 262types. 263 264### Alternatives For Lowering an n-D Vector Type to LLVM 265 266Consider a vector of rank n with static sizes `{s_0, ... s_{n-1}}` (i.e. an MLIR 267`vector<s_0x...s_{n-1}xf32>`). Lowering such an `n-D` MLIR vector type to an 268LLVM descriptor can be done by either: 269 2701. Flattening to a `1-D` vector: `!llvm<"(s_0*...*s_{n-1})xfloat">` in the MLIR 271 LLVM dialect. 2722. Nested aggregate type of `1-D` vector: 273 `!llvm."[s_0x[s_1x[...<s_{n-1}xf32>]]]">` in the MLIR LLVM dialect. 2743. A mix of both. 275 276There are multiple tradeoffs involved in choosing one or the other that we 277discuss. It is important to note that “a mix of both” immediately reduces to 278“nested aggregate type of 1-D vector” with a `vector.cast %0: 279vector<4x8x16x32xf32> to vector<4x4096xf32>` operation, that flattens the most 280"k" minor dimensions. 281 282### Constraints Inherited from LLVM (see LangRef) 283 284The first constraint was already mentioned: LLVM only supports `1-D` `vector` 285types natively. Additional constraints are related to the difference in LLVM 286between vector and aggregate types: `“Aggregate Types are a subset of derived 287types that can contain multiple member types. Arrays and structs are aggregate 288types. Vectors are not considered to be aggregate types.”.` 289 290This distinction is also reflected in some of the operations. For `1-D` vectors, 291the operations `llvm.extractelement`, `llvm.insertelement`, and 292`llvm.shufflevector` apply, with direct support for dynamic indices. For `n-D` 293vectors with `n>1`, and thus aggregate types at LLVM level, the more restrictive 294operations `llvm.extractvalue` and `llvm.insertvalue` apply, which only accept 295static indices. There is no direct shuffling support for aggregate types. 296 297The next sentence illustrates a recurrent tradeoff, also found in MLIR, between 298“value types” (subject to SSA use-def chains) and “memory types” (subject to 299aliasing and side-effects): `“Structures in memory are accessed using ‘load’ and 300‘store’ by getting a pointer to a field with the llvm.getelementptr instruction. 301Structures in registers are accessed using the llvm.extractvalue and 302llvm.insertvalue instructions.”` 303 304When transposing this to MLIR, `llvm.getelementptr` works on pointers to `n-D` 305vectors in memory. For `n-D`, vectors values that live in registers we can use 306`vector.extract` and `vector.insert` which do not accept dynamic indices. Note 307that this is consistent with hardware considerations as discussed below. 308 309An alternative is to use an LLVM `1-D` `vector` type for which one can use 310`llvm.extractelement`, `llvm.insertelement` and `llvm.shufflevector`. These 311operations accept dynamic indices. The implication is that one has to use a 312flattened lowering of an MLIR n-D vector to an LLVM 1-D vector. 313 314There are multiple tradeoffs involved that mix implications on the programming 315model, execution on actual HW and what is visible or hidden from codegen. They 316are discussed in the following sections. 317 318### Nested Aggregate 319 320Pros: 321 3221. Natural encoding n-D vector -> (n-1)-D aggregate over 1-D vector. 3232. No need for linearization / delinearization logic inserted everywhere. 3243. `llvm.insertvalue`, `llvm.extractvalue` of `(n-k)-D` aggregate is natural. 3254. `llvm.insertelement`, `llvm.extractelement`, `llvm.shufflevector` over `1-D` 326 vector type is natural. 327 328Cons: 329 3301. `llvm.insertvalue` / `llvm.extractvalue` does not accept dynamic indices but 331 only static ones. 3322. Dynamic indexing on the non-most-minor dimension requires roundtrips to 333 memory. 3343. Special intrinsics and native instructions in LLVM operate on `1-D` vectors. 335 This is not expected to be a practical limitation thanks to a `vector.cast 336 %0: vector<4x8x16x32xf32> to vector<4x4096xf32>` operation, that flattens 337 the most minor dimensions (see the bigger picture in implications on 338 codegen). 339 340### Flattened 1-D Vector Type 341 342Pros: 343 3441. `insertelement` / `extractelement` / `shufflevector` with dynamic indexing 345 is possible over the whole lowered `n-D` vector type. 3462. Supports special intrinsics and native operations. 347 348Cons: 349 3501. Requires linearization/delinearization logic everywhere, translations are 351 complex. 3522. Hides away the real HW structure behind dynamic indexing: at the end of the 353 day, HW vector sizes are generally fixed and multiple vectors will be needed 354 to hold a vector that is larger than the HW. 3553. Unlikely peephole optimizations will result in good code: arbitrary dynamic 356 accesses, especially at HW vector boundaries unlikely to result in regular 357 patterns. 358 359### Discussion 360 361#### HW Vectors and Implications on the SW and the Programming Model 362 363As of today, the LLVM model only support `1-D` vector types. This is 364unsurprising because historically, the vast majority of HW only supports `1-D` 365vector registers. We note that multiple HW vendors are in the process of 366evolving to higher-dimensional physical vectors. 367 368In the following discussion, let's assume the HW vector size is `1-D` and the SW 369vector size is `n-D`, with `n >= 1`. The same discussion would apply with `2-D` 370HW `vector` size and `n >= 2`. In this context, most HW exhibit a vector 371register file. The number of such vectors is fixed. Depending on the rank and 372sizes of the SW vector abstraction and the HW vector sizes and number of 373registers, an `n-D` SW vector type may be materialized by a mix of multiple 374`1-D` HW vector registers + memory locations at a given point in time. 375 376The implication of the physical HW constraints on the programming model are that 377one cannot index dynamically across hardware registers: a register file can 378generally not be indexed dynamically. This is because the register number is 379fixed and one either needs to unroll explicitly to obtain fixed register numbers 380or go through memory. This is a constraint familiar to CUDA programmers: when 381declaring a `private float a[4]`; and subsequently indexing with a *dynamic* 382value results in so-called **local memory** usage (i.e. roundtripping to 383memory). 384 385#### Implication on codegen 386 387MLIR `n-D` vector types are currently represented as `(n-1)-D` arrays of `1-D` 388vectors when lowered to LLVM. This introduces the consequences on static vs 389dynamic indexing discussed previously: `extractelement`, `insertelement` and 390`shufflevector` on `n-D` vectors in MLIR only support static indices. Dynamic 391indices are only supported on the most minor `1-D` vector but not the outer 392`(n-1)-D`. For other cases, explicit load / stores are required. 393 394The implications on codegen are as follows: 395 3961. Loops around `vector` values are indirect addressing of vector values, they 397 must operate on explicit load / store operations over `n-D` vector types. 3982. Once an `n-D` `vector` type is loaded into an SSA value (that may or may not 399 live in `n` registers, with or without spilling, when eventually lowered), 400 it may be unrolled to smaller `k-D` `vector` types and operations that 401 correspond to the HW. This level of MLIR codegen is related to register 402 allocation and spilling that occur much later in the LLVM pipeline. 4033. HW may support >1-D vectors with intrinsics for indirect addressing within 404 these vectors. These can be targeted thanks to explicit `vector_cast` 405 operations from MLIR `k-D` vector types and operations to LLVM `1-D` 406 vectors + intrinsics. 407 408Alternatively, we argue that directly lowering to a linearized abstraction hides 409away the codegen complexities related to memory accesses by giving a false 410impression of magical dynamic indexing across registers. Instead we prefer to 411make those very explicit in MLIR and allow codegen to explore tradeoffs. 412Different HW will require different tradeoffs in the sizes involved in steps 1., 4132. and 3. 414 415Decisions made at the MLIR level will have implications at a much later stage in 416LLVM (after register allocation). We do not envision to expose concerns related 417to modeling of register allocation and spilling to MLIR explicitly. Instead, 418each target will expose a set of "good" target operations and `n-D` vector 419types, associated with costs that `PatterRewriters` at the MLIR level will be 420able to target. Such costs at the MLIR level will be abstract and used for 421ranking, not for accurate performance modeling. In the future such costs will be 422learned. 423 424#### Implication on Lowering to Accelerators 425 426To target accelerators that support higher dimensional vectors natively, we can 427start from either `1-D` or `n-D` vectors in MLIR and use `vector.cast` to 428flatten the most minor dimensions to `1-D` `vector<Kxf32>` where `K` is an 429appropriate constant. Then, the existing lowering to LLVM-IR immediately 430applies, with extensions for accelerator-specific intrinsics. 431 432It is the role of an Accelerator-specific vector dialect (see codegen flow in 433the figure above) to lower the `vector.cast`. Accelerator -> LLVM lowering would 434then consist of a bunch of `Accelerator -> Accelerator` rewrites to perform the 435casts composed with `Accelerator -> LLVM` conversions + intrinsics that operate 436on `1-D` `vector<Kxf32>`. 437 438Some of those rewrites may need extra handling, especially if a reduction is 439involved. For example, `vector.cast %0: vector<K1x...xKnxf32> to vector<Kxf32>` 440when `K != K1 * … * Kn` and some arbitrary irregular `vector.cast %0: 441vector<4x4x17xf32> to vector<Kxf32>` may introduce masking and intra-vector 442shuffling that may not be worthwhile or even feasible, i.e. infinite cost. 443 444However `vector.cast %0: vector<K1x...xKnxf32> to vector<Kxf32>` when `K = K1 * 445… * Kn` should be close to a noop. 446 447As we start building accelerator-specific abstractions, we hope to achieve 448retargetable codegen: the same infra is used for CPU, GPU and accelerators with 449extra MLIR patterns and costs. 450 451#### Implication on calling external functions that operate on vectors 452 453It is possible (likely) that we additionally need to linearize when calling an 454external function. 455 456### Relationship to LLVM matrix type proposal. 457 458The LLVM matrix proposal was formulated 1 year ago but seemed to be somewhat 459stalled until recently. In its current form, it is limited to 2-D matrix types 460and operations are implemented with LLVM intrinsics. In contrast, MLIR sits at a 461higher level of abstraction and allows the lowering of generic operations on 462generic n-D vector types from MLIR to aggregates of 1-D LLVM vectors. In the 463future, it could make sense to lower to the LLVM matrix abstraction also for CPU 464even though MLIR will continue needing higher level abstractions. 465 466On the other hand, one should note that as MLIR is moving to LLVM, this document 467could become the unifying abstraction that people should target for 1-D vectors 468and the LLVM matrix proposal can be viewed as a subset of this work. 469 470### Conclusion 471 472The flattened 1-D vector design in the LLVM matrix proposal is good in a 473HW-specific world with special intrinsics. This is a good abstraction for 474register allocation, Instruction-Level-Parallelism and 475SoftWare-Pipelining/Modulo Scheduling optimizations at the register level. 476However MLIR codegen operates at a higher level of abstraction where we want to 477target operations on coarser-grained vectors than the HW size and on which 478unroll-and-jam is applied and patterns across multiple HW vectors can be 479matched. 480 481This makes “nested aggregate type of 1-D vector” an appealing abstraction for 482lowering from MLIR because: 483 4841. it does not hide complexity related to the buffer vs value semantics and the 485 memory subsystem and 4862. it does not rely on LLVM to magically make all the things work from a too 487 low-level abstraction. 488 489The use of special intrinsics in a `1-D` LLVM world is still available thanks to 490an explicit `vector.cast` op. 491 492## Operations 493 494[include "Dialects/VectorOps.md"] 495